Drought is not unusual in African savannas. Seasonal dry periods shape vegetation, wildlife movement, and predator–prey dynamics. What challenges ecosystems most are prolonged, multi-year droughts, when rainfall fails across consecutive seasons and water sources contract dramatically.

In the Tsavo Conservation Area, drought is one of the most significant natural pressures affecting wildlife. Some species endure through specialised behavioural or physiological adaptations. Others are far more vulnerable. Understanding these differences is essential for effective conservation planning.

Drought in Tsavo: A recurring ecological force

Tsavo has experienced repeated severe droughts over the past decades, several with profound ecological consequences.

The 1971 to 1972 drought remains one of the most historically significant. Combined with intense poaching pressure at the time, it contributed to a dramatic decline in the elephant population, which fell from an estimated 42,000 individuals to around 25,000. The 2008 to 2010 drought caused widespread wildlife mortality and significant environmental stress across the region.

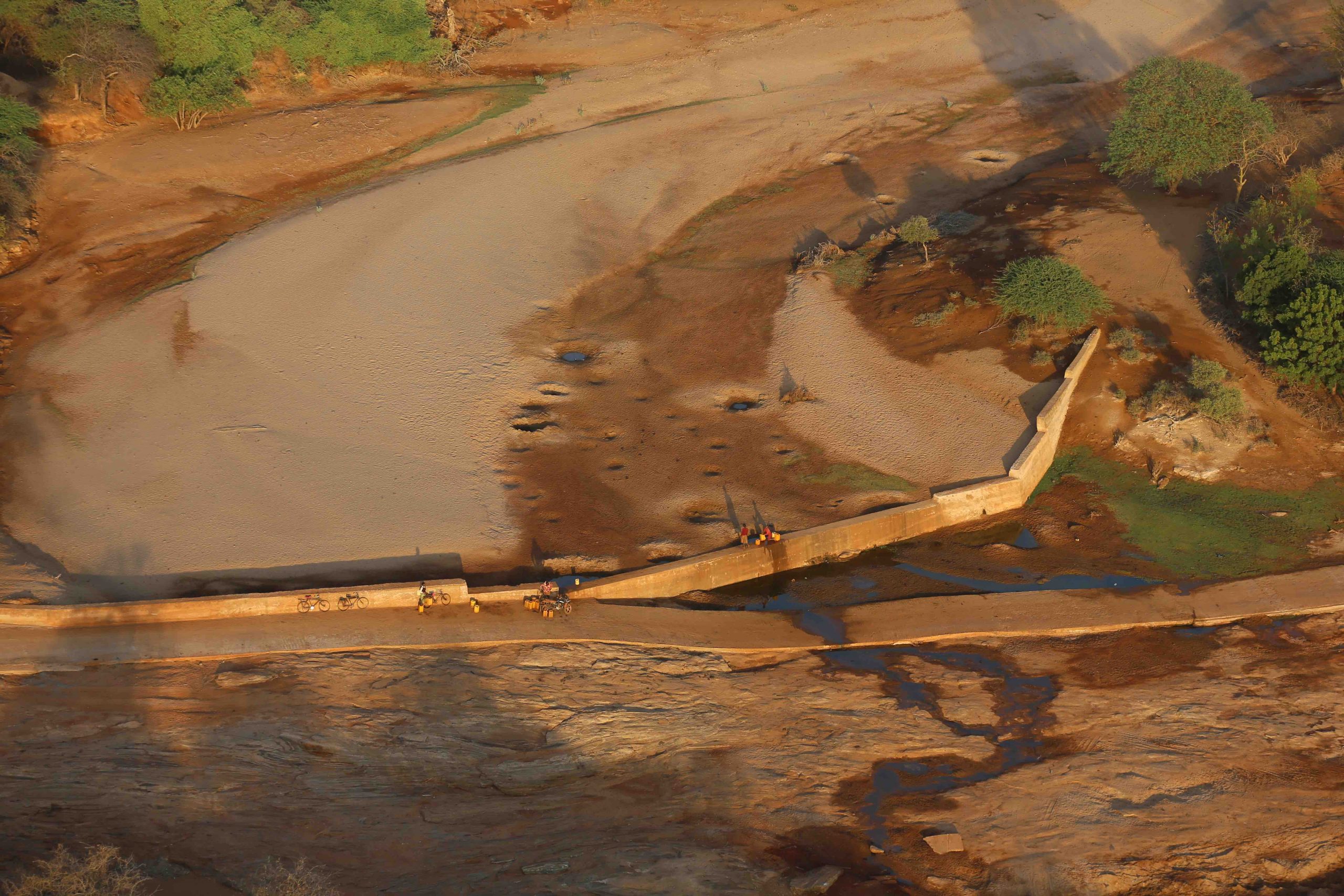

More recently, the 2020 to 2023 drought has been widely regarded as the most severe in East Africa since the 1980s. Multiple rainy seasons failed. Natural water pans, boreholes, and major water sources such as Aruba Dam dried up. Wildlife, livestock, and crops were heavily affected. During this period, 109 elephants were reported to have died from drought-related stress in Tsavo alone.

Beyond these extreme events, Tsavo also experiences predictable annual dry seasons. The primary wildfire season typically occurs between July and October, peaking in September, when vegetation dryness increases fire risk. Seasonal drought is part of the ecosystem’s natural rhythm. However, extended rainfall failure can exceed adaptive thresholds, leading to large-scale mortality and long recovery periods for slow-reproducing species.

Elephants: Movement, memory, and engineering water access

Among Africa’s large mammals, the African elephant demonstrates both vulnerability and remarkable adaptive capacity during drought.

Elephants rely on long-term spatial memory and social knowledge to locate water across vast landscapes. Matriarchs retain information about seasonal rivers, springs, and historical water points. During dry periods, herds may travel considerable distances to reach reliable sources. Movement patterns shift toward cooler hours to reduce heat stress and conserve energy. Bulls often range independently, while family groups balance calf endurance with water access.

When surface water disappears, elephants dig into sandy riverbeds to access subsurface water stored beneath the surface. Using their tusks and trunks, they excavate wells that tap into filtered groundwater. These wells frequently benefit other species, including antelope, birds, and smaller mammals. In this way, elephants function as landscape engineers.

Yet these strategies do not guarantee survival. Elephants require large volumes of water daily and depend on vegetation that rapidly declines in quality during prolonged drought. Calves, lactating females, and older individuals are typically most vulnerable. Once body condition deteriorates beyond a critical point, recovery becomes unlikely. For a species with slow reproduction, drought-related mortality can affect population structure for decades.

Aestivation: surviving drought by slowing down

Not all species respond to drought through movement. Some survive by entering a dormant state known as aestivation.

The African helmeted turtle, for example, can survive when ponds dry by burrowing into moist mud at the base of shrinking water bodies. During aestivation, metabolic rate declines, feeding stops, and activity is minimal. Energy reserves are conserved until rainfall returns. This strategy allows survival for months, though prolonged drought beyond physiological limits can still result in mortality.

Juvenile Nile crocodiles may use burrows during extreme heat and drying conditions. Retreating into shaded mud banks reduces heat exposure and water loss. While crocodiles remain more alert than aestivating turtles, prolonged drought reduces prey availability and increases competition within shrinking pools.

Fringed-eared oryx: Built for arid conditions

The fringed-eared oryx, found in Tsavo’s drier habitats, demonstrates long-term physiological adaptation to arid environments.

Oryx can tolerate elevated internal body temperatures, reducing reliance on evaporative cooling. They produce highly concentrated urine and dry dung, conserving water efficiently. Much of their moisture intake is derived from vegetation rather than direct drinking. These traits allow oryx to persist where more water-dependent grazers may decline.

Hippos and water dependence

In contrast, the hippopotamus is highly dependent on permanent water for thermoregulation and skin protection. During severe droughts in Tsavo, including around Mzima Springs, hippo populations have declined sharply when water levels dropped.

As pools shrink, animals become concentrated in remaining water sources. Crowding intensifies competition, food availability declines, and disease risk increases. In some cases, hippos are forced to travel overland under extreme heat to locate new water, further increasing stress and mortality risk. Drought therefore has disproportionate impacts on water-dependent species.

Sand dams: storing water below the surface

Natural sandy riverbeds already function as subsurface water storage systems. Sand dams build on this principle. Constructed across seasonal watercourses, they slow water flow during rains without blocking it. Sand accumulates behind the structure, forming a reservoir that stores filtered water protected from evaporation.

This stored water persists long after surface flows cease. Wildlife, including elephants, can dig into these sand-filled areas during dry periods. In Tsavo, sand dam projects are part of broader efforts to strengthen landscape resilience, supporting both wildlife and neighbouring communities during extended dry spells.

The Limits of Adaptation

Savanna species evolved under variable rainfall regimes. Movement, aestivation, physiological tolerance, and water engineering are products of long-term adaptation. However, increasing climate variability may intensify drought frequency and duration beyond historical norms.

When drought becomes more prolonged and severe, even well-adapted species reach survival thresholds. For slow-reproducing animals such as elephants, recovery from severe mortality events can take decades.

Drought shapes Tsavo’s ecology. Some species survive through mobility, some through dormancy, and others through physiological efficiency. Effective conservation depends on understanding these strategies and strengthening the ecological processes that buffer extreme dry periods.